ANCIENT BEAUTY ICONS: GODDESSES AND QUEENS

Antiquity and Modern Beauty Standards

The enduring popularity of antiquity in modern cosmetics is due mostly to several prominent mythological and historical figures who are associated with beauty: namely, the Greek goddess Aphrodite and her Roman counterpart Venus; and the Egyptian rulers Nefertiti and Cleopatra. This section will survey how these figures are represented in modern makeup and their simultaneous enforcement and dismantling of classical beauty ideals, focusing on the topic of skin color. Particular emphasis will be placed on how portrayals of Egyptian queens in makeup advertising corresponded to racial identity.

As noted in the exhibition background, makeup in the ancient Western world was typically used by middle and upper-class women to achieve what was considered beauty at the time, i.e. a pale, youthful complexion, rosy cheeks and lips, and lightly defined eyelashes and brows. According to the belief system of their respective eras, these features were naturally embodied by Aphrodite and Venus. In turn, goddesses representing beauty were consistently portrayed in Western art - especially during the Renaissance and Neo-Classical eras - with these qualities, thus defining the classical aesthetic.(1) The connotations between white, wrinkle-free skin, Eurocentric facial features and goddess-like beauty proliferated in makeup advertising throughout the 20th century. Many ads and collections referred to the beauty displayed by Greco-Roman statues. For one fashion designer’s show in 1940, the models’ makeup was applied to emulate ancient sculptures. “[The] soft even glow of the old marbles was the ideal sought, as well as eyebrows and mouth contours like those of the sculptured masterpieces; and powders and rouges were suggested accordingly.”(2) Several ads have no text at all, instead choosing to show a perfectly smooth marble statue or juxtapose a closeup of a white woman’s face with an image of the Venus de Milo. The emphasis on ancient sculptures’ whiteness as ideal beauty is in keeping with the white supremacist tradition of ignoring what these statues actually looked like: sculptures were often painted bright colors. As historian Sarah Bond points out, Eurocentric art historians like Johann Winckelmann and other influential scholars “perpetuated and further entrenched the idea that white marble statues like the famed Apollo of the Belvedere were the epitome of beauty.”

Ads for Lancome (1939) and Dorin (1945). Purchased from hprints.com.

Definitions of goddess beauty were adjusted to promote the latest makeup styles and products while adhering to traditional beauty ideals. By declaring a collection or shade to be those of a “modern goddess”, cosmetic companies appeared to be updating notions of classical beauty, but in reality, merely reinforced white supremacist standards. The model in Aziza’s 1967 Shades of Venus ad, for example, wears heavy green eyeliner and matte eyeshadow. The style reflects the aesthetic of its time rather than antiquity, but doesn’t actually redefine goddess beauty. The ad notes that the “modern Venus lives and loves, sings and swings the way no classic beauty ever did” yet shows a conventionally pretty white model. In short, “white supremacy has weaponized the classical tradition, and its definitions of beauty,” states Grace McGowan.(3)

However, while Aphrodite and Venus were consistently presented as fair-skinned, the bulk of depictions of whiteness as a beauty ideal was in Egyptian themed cosmetics. Many Western makeup brands portrayed Cleopatra and Nefertiti as exotic and mysterious to sell products to a white audience. As summarized earlier, makeup used by the ancient Egyptians was different than in the West. The early 20th century cosmetics industry was quick to capitalize on traditional Egyptian beauty practices by depicting them and the culture from which they originated as “other”, making them attractive to Western consumers. Beauty companies’ interpretation of ancient Egypt ironically ended up centering whiteness. In her paper entitled “Is Cleopatra Black?” Angelica Maier explains how perceptions of the ancient queen were dictated by white hegemony in the U.S. during the 1920s.(4) “The question of Cleopatra’s race is what allowed Orientalist depictions of her to be appropriated into whiteness; in an American context, an ‘Oriental’ queen translated into a white aspirational figure of modernity. In other words, depictions of Cleopatra transformed racial otherness into white feminine power. For new women, Cleopatra’s independence and power (linked with her beauty) underscored her desirability…the more exotic motifs one wears, the more ‘white’ one becomes.” Maier concludes that 1920s fashion and makeup advertising gave “white women the power to exude sexuality in an acceptable way through both her high-class status and the cultural appropriation of Cleopatra into whiteness,” and that “the wearer continually becomes white” via the wearing of Egyptian-inspired fashion and makeup. This phenomenon was especially apparent in the advertising for Nysis and Palmolive. Their ads feature a variety of tan-skinned men and women – who in turn can be interpreted as enslaved - catering to pale white women.(5) This imagery dates back at least to the Renaissance and is still used today. In portraying people of color as nothing more than sexualized props, they uphold the traditional link between white skin and exclusive access to beauty, power and status.

Nysis and and Palmolive ads, 1920.

Some companies also insisted that Cleopatra was never Egyptian to begin with, subscribing to the belief that her racial identity was white. According to one early 1920s brochure for Tokalon beauty products, “Cleopatra was the daughter of Ptolemy, a descent of one of the generals of Alexander the Great. Therefore she was a Macedonian and no Egyptian blood flowed in her veins, and instead of having black hair and large, dark, dreamy eyes, with which most persons associate her, she probably had dark brown hair, blue eyes, and a fair skin[.]” The figure of Cleopatra, in some cases, therefore strengthened white supremacist beauty ideals.

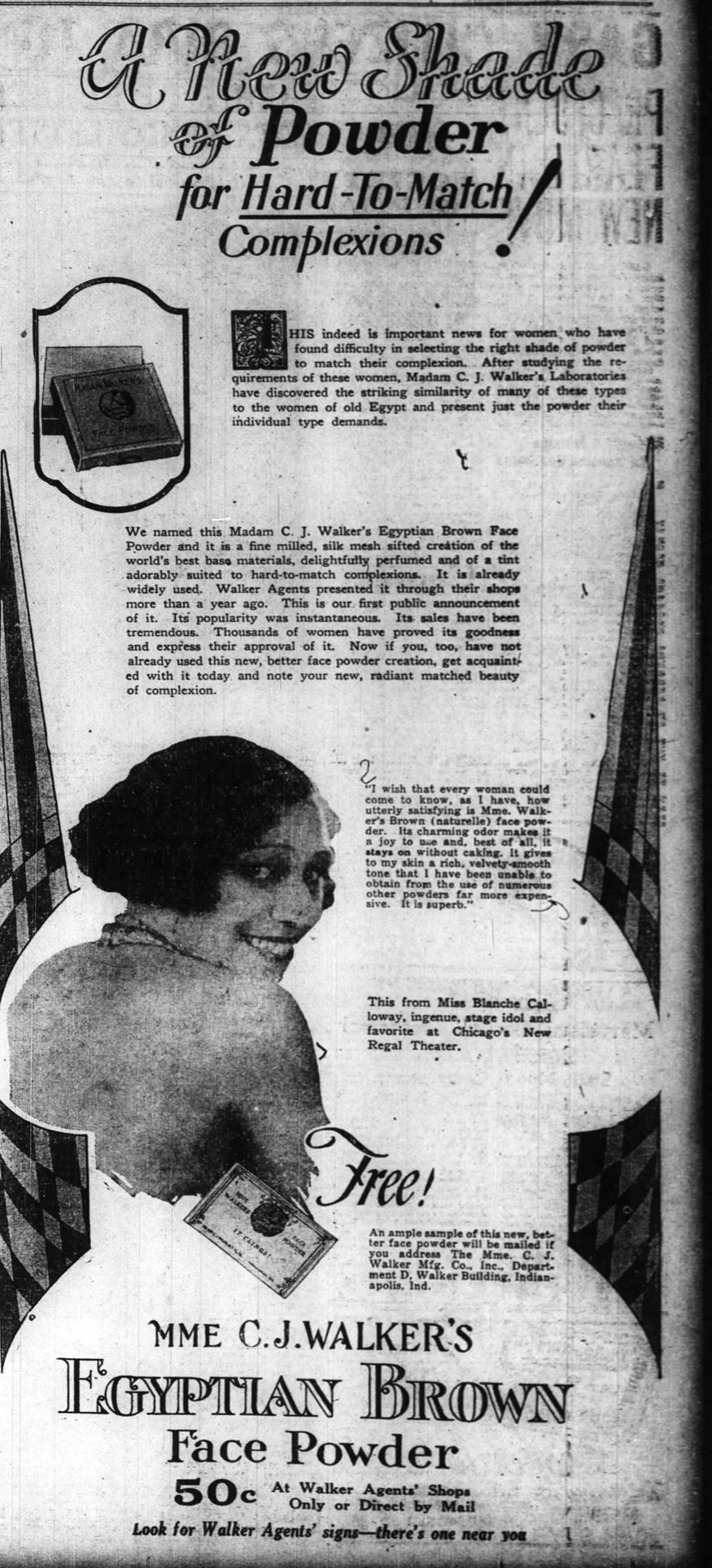

Despite this narrative, the Black community attempted to reclaim Cleopatra and Nefertiti from the clutches of white beauty standards. Kashmir Chemical Company’s Nile Queen brand was possibly the first cosmetics line to utilize the Black “interest in Cleopatra and the African origins of Egyptian culture,” and “drew reference to the famous Egyptian Cleopatra, marketing its namesake as ‘Kleopatra, Queen of the Nile, The World’s Famous Brown Beauty.’ Exoticizing Cleopatra as a ‘dusky beauty’ and a ‘beautiful creature of African birth,’ Nile Queen claimed ‘brown beauty’ as the heritage of African descended women.”(6) Madam C.J. Walker’s advertising for their Egyptian Brown powder eschewed direct references to Black skin, opting instead for euphemisms such as “hard-to-match complexions”. However, Walker’s ad also linked deeper skintones to those of ancient Egyptian women, stating that the company’s labs had unearthed a “striking similarity of many of these types to the women of old Egypt”. This is in keeping with the concept that ancient Egypt is in fact part of Black history. As Alys Eve Weinbaum notes, “[The] subversive idea of Black Egypt as the archetype of civilization at its most beautiful and advanced (an idea popularized in aesthetics, literature and pageantry associated with the Harlem Renaissance) is adumbrated.”(7)

Newspaper ad for Madam C.J. Walker’s Egyptian Brown face powder, The Pittsburgh Courier, July 14, 1928.

Several cosmetics companies continued this notion some 60 years after Kashmir and Madam Walker. Flori Roberts, a brand created for Black women in 1965, introduced “Cleopatra Colors” in 1981. The marketing implied that non-white women possessed a unique beauty that dated to antiquity. “Since Cleopatra, the mystery and beauty of women of color has been held in awe. Today Flori Roberts translates this mystery into reality with special makeup and makeup techniques.”(8) That same year, actress turned beauty entrepreneur Barbara Walden released Easy Glamour: The Black Woman’s Definitive Guide to Beauty and Style, which noted that “dusky-skinned Egyptian women” were the first to develop a beauty routine. The book referenced Walden’s own line of products, such as Egyptian Almond scrub, and tips specifically for Black women on how to modernize Egyptian makeup and hair styles.(9)

While some brands fostered the connection between ancient Egypt and Black beauty, tawny skin remained acceptable only as long as it was temporarily worn by white women, who began embracing the tan in the 1920s as it became synonymous with a life of leisure. A summer tan became integrated to classical notions of beauty as cosmetic companies realized they could offer more affordable ways for the average customer to achieve sun-kissed skin than spending a month on the Amalfi Coast. In an article on how to prepare beauty-wise for summer, Harper’s Bazaar suggests several fake tanning products and notes, “To match the beauty of the golden days we’re counting on this summer, you must rise like Venus from the foam – a latter-day Venus, taut and slim and honey-beige.”(10) Makeup brands continued associating tan skin with goddess beauty. Estée Lauder launched their Bronze Goddess line of bronzing powder and self-tanner in 2000. Today the collection is released annually and features dozens of accompanying products.

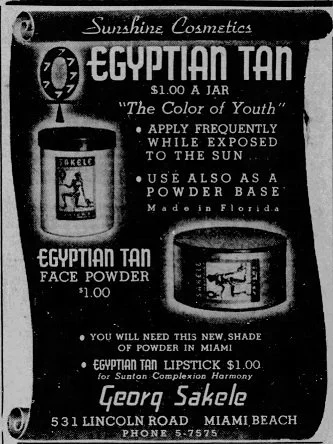

Deeper shades of face powder intended for white women wanting to fake a tan were sometimes named Egyptian, a tactic that may have been stolen from Kashmir and Madam C.J. Walker. In 1938 a “beauty specialist” named Georg Sakele introduced a trio of products for fair-skinned customers who would prefer to be darker in the summer months. “Sakele’s first problem is to help charming women from all over America to acquire a beautiful tan without a painful sunburn. For this he has developed ‘Egyptian Tan Crème,’ said to contain a harmless ingredient that screens out more than 90% of the sun’s rays, thus preventing painful sunburn, yet admitting enough rays to provide a beautiful tan. After acquiring the tan, no ordinary face powder or lipstick is suitable. So to complete the ensemble, Sakele blends his ‘Egyptian Tan Face Powder’ and ‘Egyptian Tan Lipstick’ of colors and textures specifically suited to the patron’s new complexion.”(11)

Newspaper ad for Egyptian Tan cosmetics, The Miami Herald, January 29, 1939.

A year later, Tayton released a new shade called Egyptian “especially for brunettes”. In the early 1940s Max Factor Studios created a hue called Light Egyptian for actress Lena Horne, whose skin tone, movie executives felt, was not dark enough for a mixed-race actress. According to Horne, Max Factor’s creation resulted in white actresses using it to play multi-racial characters.(12) Even in the early 2000s, several lines intended for professional makeup artists listed Light Egyptian and Dark Egyptian as shades.(13) In these contexts, the concept of the bronze goddess was intended only for white women as a means of displaying their status, while “Egyptian” shades granted them the ability to essentially cosplay a different identity. “Even when ‘exotic’ types like Sheba and Cleopatra were featured as suntans became fashionable, such choices were just that – fun looks white women could choose at will,” observes Susannah Walker in In Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920–1975.(14) Additionally, regardless of their advertising that celebrated Black beauty and linked it to ancient Egypt, Kashmir Chemical Company and others used lighter-skinned models. Flori Roberts was a white woman who exploited the gatekeeping of Black-owned beauty companies that prevented them from entering the mainstream cosmetics arena.

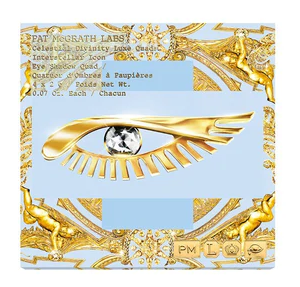

However, Black reclamation of both ancient Egyptian culture and the classical goddess aesthetic continued into the 21st century, providing a means of diversifying the beauty standard of pale skin. In 1970 Astarte, a brand intended for women of color, was launched and accompanied by an ad campaign featuring a striking image of Black model Pat Evans. According to one article, the Astarte line was named for a “dark-complexioned Phoenician goddess”.(15)Makeup artist Kevyn Aucoin transformed singer Tina Turner into Cleopatra in his book Face Forward (2000). Performers Beyoncé and Lizzo donned goddess costumes and makeup in 2017 and 2021, respectively. Juvia’s Place, a brand founded in 2016, offers a “Nubian” collection featuring illustrations of Nefertiti on the packaging. Pat McGrath uses one of her most iconic looks as the logo for her makeup line: an outline of the Egyptian-inspired eye she created for Dior’s spring 2004 couture show. While it’s merely speculation that McGrath intentionally tried to make a connection between Egyptian makeup and Blackness in selecting this style out of all her others, the choice may not have been entirely accidental either.

Pat McGrath eyeshadow palette packaging featuring an elaborate gold-lined almond shaped eye motif. The diamond “iris” and ornate gold and diamond statuary surrounding the eye heightens the sense of luxury.

Monica S. Cyrino, Aphrodite (New York: Routledge, 2010) 130-32.

“Fashion show of Clothes for Tall Women Plays Up the ‘Goddess Look’: Cocktail show at Helena Rubinstein Salon Presents Dresses, Shoes, Bags, Hats, Jewelry, make-Up, Coiffure and Exercises for this ‘Typical but Neglected American Type.’” Women’s Wear Daily, Sep 13, 1940, 6, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/fashion-show-clothes-tall-women-plays-up-goddess/docview/1654242803/se-2.

Grace McGowan, “The Black Venus: Josephine Baker and Early Twentieth Century Cosmetics” presented at the conference “I’m Your Venus: The Reception of Antiquity in Modern Cosmetic Advertising and Marketing”, 7-9 September 2022.

Angelica J. Maier “’Is Cleopatra Black?’: Examining Whiteness and the American New Woman.” Humanities 10, no. 2 (2021): 68 https://doi.org/10.3390/h10020068

For more on skin color in ancient Greece and Egypt, see Maryann Eaverly, Tan Men/Pale Women: Color and Gender in Archaic Greece and Egypt: A Comparative Approach. University of Michigan Press: 2013.

Laila Haidarali, Brown Beauty: Color, Sex, and Race from the Harlem Renaissance to World War II (New York: NYU Press, 2018) 97.

Alys Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger, Madeleine Y. Dong, and Tani E. Barlow, “The Modern Girl Around the World: Cosmetics Advertising and the Politics of Race and Style,” in The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 44.

Flori Roberts, The Tennessean, 23 July 1978, 11-A.

Barbara Walden, Easy Glamour: The Black Woman’s Definitive Guide to Beauty and Style (New York: William Morrow, 1981) 20-25, 81.

“A Place in the Sun.” Harper's Bazaar, 05, 1947, 44-45, 79. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/place-sun/docview/2020138523/se-2 \

Haidarali, Brown Beauty, 94: “The industry flooded the U.S. market with images of (made-up) brown-skinned Nubian princesses and Indian maidens at once supplying mythologies of the regal, remote and colonized. Never once was the suntanned complexion marketed in the United States as an emulation of the lowly and local: the African American complexion.”

“Sakele’s Miami Beach Salon and Beauty Clinic.” The Miami Herald, 20 February 1939, 9.

Adrienne L. MacLean, All for Beauty: Makeup and Hairdressing in Hollywood’s Studio Era (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2022) 287.

Susannah Walker, Style and Status: Selling Beauty to the African-American Woman, 1920-1975 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007) 40.

Jean Ehmsen, “Cosmetic Firms Eye Big Money in the Negro Market,” 7 Oct. 1970, 4D.